Developer left in the dark as builder garnishes $11 Million from developer’s bank account without notice

In the recent decision of Fitz Jersey Pty Ltd v Atlas Construction Group Pty Ltd [2017] NSWCA 53 a Contractor was able to garnish $11 million from the Principal’s bank account using the NSW security of payment legislation.

The Principal was caught by surprise because at the time the money was garnished from its bank account the Principal had already commenced legal proceedings seeking judicial review of the adjudication determination and the Contractor provided no prior notice to the Principal that it had sought and obtained a garnishee order. The Court found a judgement obtained by registering an adjudication determination can be enforced without notice to an affected party and that the Contractor was not required to notify the Court about the proceedings commenced by the Principal in applying for the garnishee order.

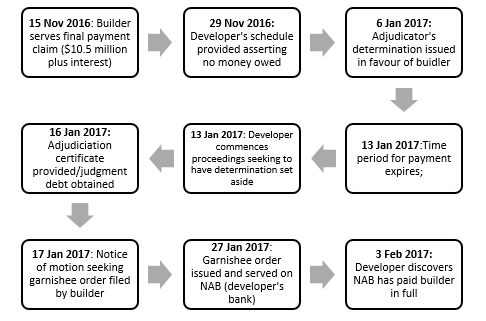

Chronology of events

Facts

The applicant, Fitz Jersey (“the developer”) and the respondent, Atlas Construction Group (“the builder”) entered into a design and construct contract in December 2010. The builder served a final payment claim of $11 million on the developer on 15 November 2016, pursuant to the Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) (“Security of Payment Act”). An adjudication determination was handed down in favour of the builder. The developer failed to make payment within the allocated time period, but commenced proceedings in the Equity Division of the Supreme Court, seeking to have the determination set aside on the basis of jurisdictional error prior to the builder registering the adjudicator’s determination as a judgement. A declaration was sought that the determination was void but no request for an injunction to stop payment or an undertaking to that effect was sought.

In the interim and despite the commencement of legal proceedings, the builder filed an adjudication certificate1, in the Supreme Court as a judgment debt2, and obtained a garnishee order to enforce the adjudication determination. Without the developer’s knowledge, NAB had paid $11 million to the builder, prior to the resolution of the proceedings in the Supreme Court regarding jurisdictional error in the Adjudication determination.

After Justice McDougall’s first instance decision in favour of the builder, the developers appealed, arguing:

- Notice was impliedly required to be given to the developer when the builder obtained the judgment debt in order to avoid s 25(4) being rendered nugatory;

- The proceedings in which the developer was challenging the adjudication determination should have been disclosed to the court;

- The primary judge should have set aside the garnishee order and ordered repayment to the developer.

Decision: appeal dismissed

a) Notice

The Court of Appeal held that the builder was not required to give notice that the adjudication determination had been registered and was under no obligation to notify the developer that it was taking enforcement steps. As a result, the judgment could be enforced via the garnishee order without it having been served on the developer.

The Court held that section 25(4) of the Security of Payment Act does not grant any right to have an adjudication determination set aside. Instead, it provides an entitlement to seek relief.

The section could not be interpreted as placing a respondent in any better position than an unsuccessful respondent against whom a judgement debt has been obtained in civil proceedings. In fact, the purpose of the section is to restrict the grounds which would otherwise be available in such proceedings. This is consistent with the pay now fight (or dispute) later nature of the security of payment act regime.

b) Duty of candour

The Court held that the builder was not under any duty to disclose the fact that the developer had filed proceedings when seeking a garnishee order. The Court of Appeal emphasised the distinction between ex parte applications for injunctive relief and garnishee orders and the differing disclosure requirements. The Court noted that there may be circumstances where a party would be under a duty to disclose. For example, circumstances which would disentitle the party to relief or circumstances where a stay has been sought or foreshadowed in discussions between the parties should be disclosed. However, because in this case those circumstances did not arise, the builder was not required to inform the court of the proceedings.

Lessons to be learned

This case serves as an important reminder that timing is crucial when it comes to preventing enforcement. As demonstrated by this case, an adjudication determination in NSW can be handed down, filed and enforced via a garnishee order within a three week period. Principals should be aware of the avenues available to them and should act quickly if they intend to successfully challenge an adjudication determination before it is enforced.

Notice of the filing of an adjudication determination or an intention to enforce an adjudication certificate is not required to be given. Additionally, even if a principal has commenced proceedings challenging the validity of the underlying adjudication determination forming the basis of any application for enforcement orders, the existence of these proceedings do not need to be disclosed to the court.

Where there is a dispute as to the validity of an adjudication determination, it is clear that the onus will rest entirely on the principal to seek to prevent its enforcement. While proceedings can be issued to attempt to have a determination set aside, these proceedings alone cannot be relied upon by the principal to prevent enforcement. Instead, the principal must take additional, proactive steps to protect itself.

Where a principal finds itself in this position, it should communicate immediately with the other party and request an undertaking not to enforce the adjudication determination until a resolution has been reached. At the very least, the principal should obtain an undertaking from the other party that ensures notice will be given of any steps taken to enforce the adjudicator’s decision.

If an undertaking cannot be obtained, the principal should consider seeking interlocutory relief to prevent enforcement, in the form of an application for a stay of proceedings. This process should be commenced immediately where a principal has decided to challenge the validity of the adjudication determination.

However, the difficulty that a principal is likely to encounter in obtaining this relief was also brought home by this case. Although there was no evidence that the builder would have been unable to repay the $11 million final payment, even if evidence were available to this effect, it is likely that the objects of the Security of Payment legislation would prevent relief being ordered. As the legislation requires the risk of insolvency to be borne by the principal, convincing the Supreme Court of the need for a stay may prove difficult. This case suggests additional arguments will be necessary.

1 Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) s 23.

2 Building and Construction Industry Security of Payment Act 1999 (NSW) s 24(1)(a).