A new challenger enters the arena: why the CCIV is poised to dethrone the MIS as the preferred funds management structure

On 10 February 2022, after numerous rounds of feedback, the Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle Framework and Other Measures Bill 2021 (Cth) (CCIV Bill), passed both Houses of Federal Parliament and came quietly into being – its impact on the Australian funds landscape will undoubtedly be anything but.

The CCIV Bill establishes the corporate collective investment vehicle (CCIV), a new type of company limited by shares and specifically designed for use in funds management. The CCIV promises to act as a direct competitor to the classic managed investment scheme (MIS) structure.

Background

In the international funds sphere, it has been recognised for over a decade that Australia’s use of the MIS as the structuring model for funds is both unfamiliar and undesirable to foreign investors. This has arguably caused a number of missed investment opportunities for Australian funds. With the recent groundbreaking introduction of the variable capital company (VCC) in Singapore, and events such as the Brisbane 2032 Olympics on the horizon, the CCIV has been introduced to grant Australia an internationally recognisable and lucrative investment vehicle for use by fund managers.

How the CCIV operates

The CCIV utilises a company structure limited by shares instead of a trust structure, so as to be more recognisable to international investors than the utilisation of a head trust. As a company, a CCIV will generally be subject to the ordinary company rules under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) unless otherwise specified.

A new Chapter 8B will be added to the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) outlining the establishment and regulatory requirements of CCIVs. Amendments to other supporting legislation[1] has also been made to support the introduction of the CCIV, including ensuring that it is able to take advantage of the same flow-through tax treatment as a MIS, with the intent being that the tax outcome be the same for an investor in a sub-fund of a CCIV and an investor in an AMIT.

The result is a company structure that supports the creation of ‘single responsible entity’ sub-funds, each of which has segregated assets and liabilities, is treated as a separate entity for tax purposes, and is able to pass on franking credits, discounted capital gains and foreign income tax offsets to investors.

Acquisition of an interest in a CCIV is not regulated by the procedural rules and obligations regarding takeovers, compulsory acquisitions and buy-outs. CCIVs are further distinguished from the regular company structure by requiring the appointment of a single corporate director, in keeping with other similar international models (all of which is in stark contrast to the standard company rules under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth)).

Additionally, while CCIVs must have share capital, they are able to issue some or all of their shares as being redeemable on the member’s option, which is comparable to a member’s right to withdraw from a registered scheme. It is also generally permitted to engage in cross-investment between the sub-funds of the CCIV, where one sub-fund is able to acquire one or more shares in another of the sub-funds, and hold these as an asset of the acquiring sub-fund.

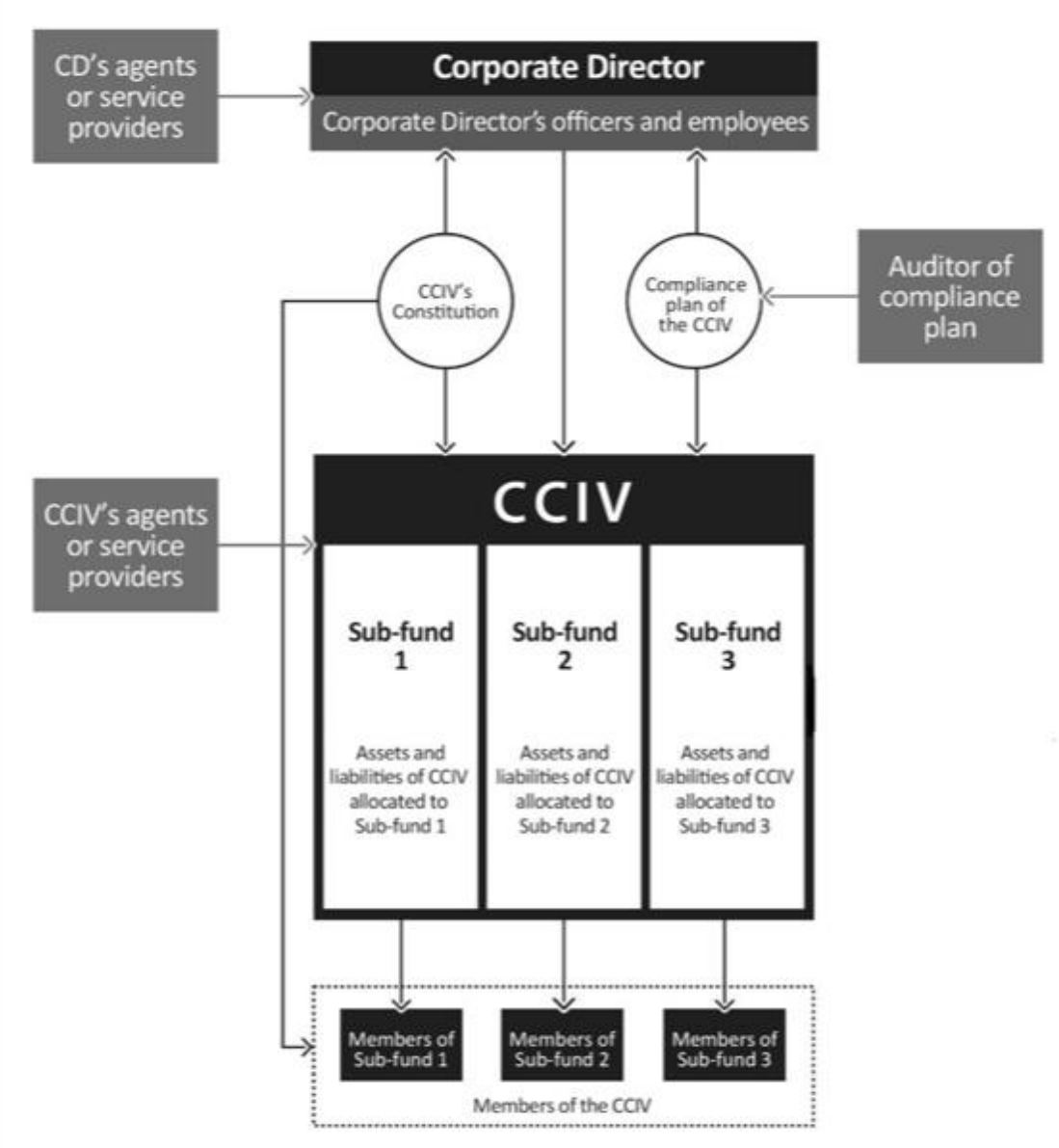

The CCIV Structure[2]

Significance for the Australian funds industry

Essentially, this piece of legislation has supported the creation of a more familiar and commercially viable investment vehicle that will provide comfort to foreign investors, and be able to compete in the international market. While a CCIV is limited by shares, and is able to be listed on the ASX, it still retains some features that correlate with the MIS, such as having a single corporate director (rather than a corporate trustee), having the ability to qualify and benefit from AMIT tax treatment, and being divided into retail and wholesale categories with different disclosure and regulatory requirements.

On top of this, the ability to invest between sub-funds, which are treated as separate tax entities, allows for additional structuring options, such as a master-feeder or hedging arrangement. This ability to build a portfolio of legally distinct but potentially mutually supporting sub-funds allows a fund manager great flexibility and the potential to utilise the benefit of economies of scale as their fund grows. Fund managers are also not limited in their management of fund from a share issuing standpoint – many of the rules that apply to issuing or reducing share capital in an ordinary company do not apply to CCIVs given its variable capital nature. CCIVs also have the option to run with a closed-ended structure, where the share capital is fixed or limited.

Next steps and practical guidance

The CCIV may present a number of unknowns to the Australian funds manager, ranging from how it is set up, to its compliance and disclosure requirements, to the potential structuring options that may be ideal for their investment portfolio.

While the MIS will no doubt continue to have a place within the Australian funds space, it is undeniable that the paradigm has shifted towards this new investment vehicle. The increased international connectivity in today’s investment landscape, coupled with the fact that the CCIV Bill is essentially a ‘Greatest Hits’ compilation of other internationally successful fund structuring options, means that utilising this structure for future funds opportunities is an opportunity that should not be overlooked.

Authored by:

Susan Forrest, Partner

Shantal Evans, Partner

Chris Dirckze, Director

Cameron Jones, Graduate

[1] Such as the Australian Securities and Investments Commission Act 2001, Personal Property Securities Act 2009, A New Tax System (Australian Business Number) Act 1999, Income Tax Assessment Act and Taxation Administration Act 1953.

[2] Corporate Collective Investment Vehicle Framework and Other Measures Bill 2021, Explanatory Memorandum, Diagram 1.1: Regulatory framework for a CCIV.