Introduction of the Scams Prevention Framework

Scams represent a growing risk to Australians in an increasingly connected world, with losses from scams totalling approximately $2.7 billion to consumers in 2023. While various regulators, such as ASIC and the ACCC, both aided by the National Anti-Scam Centre, have made it clear that combatting scams is a priority in recent years, the passage of the Scams Prevention Framework Bill 2025 (Cth) (the Bill) in February recognises the role that industry and consumers can play in combatting scams.

The Bill primarily amends the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 (Cth) (the CCA) to establish the Scams Prevention Framework (the Framework), imposing strong obligations, penalties for non-compliance, and dispute resolution pathways for consumers seeking redress.

In this article, we will set out the principles of the Framework, the regulatory structure that underlies the Framework, and what it means for regulated entities captured by the Framework.

What is captured by the Framework?

The Framework defines a scam as a “direct or indirect attempt (whether or not successful) to engage an SPF consumer of a regulated service” where it is reasonable to conclude that the attempt involves deception, and would cause loss of harm if successful. For the purposes of the Framework, a SPF (“Scams Prevention Framework”) consumer is a natural person or small business operator that is provided a service in Australia, or an Australian resident that is provided a service outside of Australia by a regulated entity that satisfies certain residency requirements.

Who does the Framework apply to?

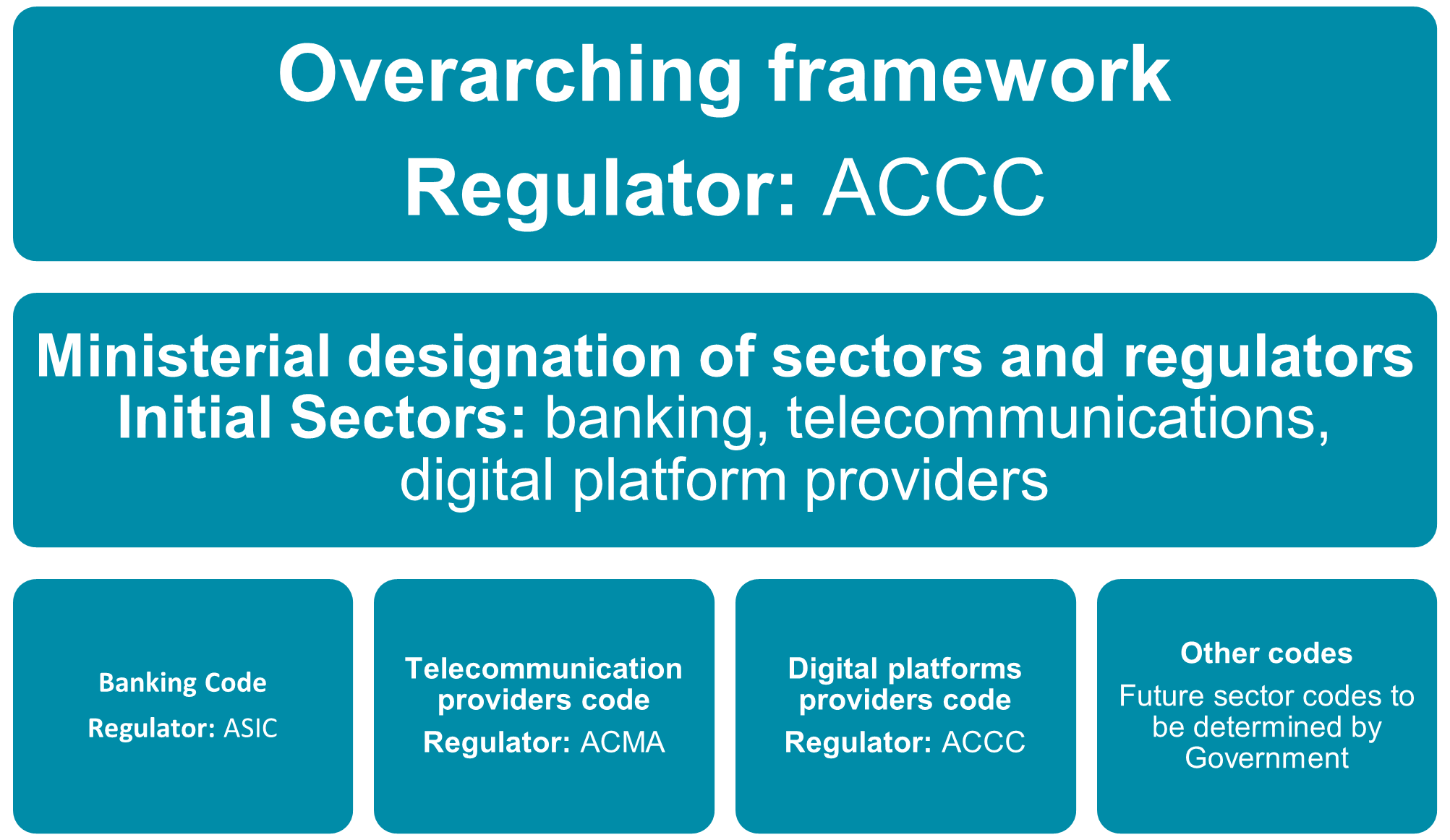

The Framework will initially apply to banks, telecommunication providers, and digital platform services (being social media, paid search engine advertising, and direct messaging services).

While the Framework only applies to these sectors initially, further sectors may be brought into the Framework over time depending on shifts in the volume of scam activity. It may be the case that the Framework will be expanded to include additional areas, such as superannuation funds, digital currency exchanges, payment providers, and transaction-based digital platforms. This decision is likely to be based on scam activity, efficacy of existing industry initiatives, the best interests of consumers, and the risks and benefits of expanding the scope of the Framework.

When is it effective?

The legislation came into force from 21 February 2025, following its royal assent, however regulated entities are not subject to the Framework until the Framework rules and sector codes have been prepared, and until their sectors are designated. The Framework requires that industry be consulted through the drafting of the Framework rules and relevant sector codes, which will provide industry participants with the opportunity to make submissions as to the way in which the Framework should apply. It is not expected for the Framework to be effective until 2026.

Framework principles

The Framework establishes six general principle-based obligations to apply to regulated entities in their treatment of scams, with various obligations that may apply. Broadly, these principles are:

- Prevent: a regulated entity is required to take reasonable steps to prevent scam activity from impacting consumers. The types of steps that a regulated entity may take will vary, but are likely to include the introduction of robust systems and appropriate procedures to prevent scammers from accessing or utilising its platform to undertake scam activities, as well as ensuring thorough education of employees and consumers;

- Detect: a regulated entity is required to take reasonable steps to detect scams, which may include identifying consumers that may be impacted by a scam in a timely manner, as well as detecting scams either before, or shortly after they have occurred;

- Report: a regulated entity is required to report and share information relating to possible detected scam activity (defined under the framework as ‘actionable scam intelligence’) to the ACCC;

- Disrupt: a regulated entity is required to take reasonable steps to disrupt suspected scams to prevent losses to consumers, which may include the introduction of measures to increase the likelihood of scam disruption. To facilitate this principle, the Framework includes a 28-day safe-harbour protection to allow regulated entities to take proportionate disruptive steps during an investigation into activity that is in progress;

- Respond: a regulated entity is required to have mechanisms for consumers to report scams, as well as an accessible internal dispute resolution (IDR) mechanism for consumers to make complaints about scams, and the regulated entity’s conduct relating to scams. Regulated entities are also required to become a member of an external dispute resolution (EDR) scheme, with AFCA to serve as the scheme for the initial sectors under the Framework; and

- Governance: a regulated entity is required to develop and implement governance policies, procedures, targets, and metrics to combat scams, with the expectation that policies and procedures are documented and dynamic to adapt as the risk of scams changes over time.

There are civil penalty provisions should a regulated entity fail to comply with the principles.

Sector-specific requirements, referred to as SPF codes, may be made by the Treasury Minister, being requirements that are geared towards the specific nature of particular sectors and the way in which they might prevent, detect, report, disrupt, and respond to scams. While these sector codes are currently being developed, Treasury has indicated that additional obligations may include the following:

- Telecommunications: implement anti-scam filters to block SMS messages that contain known phishing links;

- Digital platforms: require that advertisers of financial products have an Australian Financial Services Licence; and

- Banks: implement technology to help consumers be confident that payments are being made to the intended recipients.

Administration and enforcement of the Framework

The Framework takes a tiered approach to regulation, involving the ACCC, ACMA, and ASIC to enforce various aspects, depending on the applicable sector, which will leverage existing relationships and infrastructure.

Under the Framework, regulators will be required to make arrangements to manage risks, such as inconsistent regulatory and enforcement approaches, duplication in enforcement activity, and unclear responsibilities. The respective regulators will be permitted to share information relating to the Framework, without needing to comply with notification requirements to those affected, as well as with the ACCC, which will be able to share with various regulated entities as required.

Compensation for those affected by scams

The Framework does not require that regulated entities compensate victims of scams, however it does require that both IDR and EDR mechanisms are in place for consumers. Consumers will also be able to pursue court action when affected by a scam.

It is intended that IDR will be driven by a ‘no wrong door’ principle, meaning that consumers will be empowered to make a complaint to any business involved in or connected with the scam, and that businesses will be required to cooperate in good faith to resolve a complaint. Consumers will also have access to EDR.

The Framework requires regulated entities to comply with the Framework principles and provide consumers with a ‘statement of compliance’ during the IDR process. Where a regulated entity indicates failure to comply with the obligations, it is expected that they will either compensate consumers for scam losses, or provide justification for not doing so.

AFCA will serve as the single EDR body for the three initial sectors, to provide consumers with a ‘holistic experience’ and will allow the approach to complaints to be consistent. AFCA will be expected to consider the “actions of each business connected to a scam complaint” and award compensation proportionately, as it currently does in financial complaints. AFCA has been selected as the EDR body given its existing relationships with the handling of complaints in the financial services sector, which includes the handling of complaints relating to scams. In 2023-2024 financial year, AFCA resolved 10,400 complaints relating to scams.

Key penalties for non-compliance

The Framework acknowledges that the contravention of certain principles have the capability to create significant harm to consumers, whereas other contraventions reflect inadequate systems and processes. To that end, the Framework imposes two tiers of civil penalties.

| Maximum penalty for an entity | Maximum penalty for an individual | |

|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 contravention Breaches of the principle-based obligations relating to preventing, detecting, disrupting, and responding to scams | The greater of:

| $2,636,700 |

| Tier 2 contravention Breaches of the principle-based obligations relating to reporting and governance, and any breaches of the sector codes | The greater of:

| $528,000 |

What this means for regulated entities

While the Framework does not apply to regulated entities until they are designated, it is currently unclear whether there will be a transition period to allow entities to prepare and implement tools and strategies to be compliant. As a result, regulated entities, and those that are likely to be added due to scam activity in their industries (such as superannuation, insurance, cryptocurrency, and online marketplace providers) should take steps now to ensure they are able to quickly comply when required.

Activities that should be undertaken now, may include:

- participating in government consultation relating to the Framework rules and applicable sector-specific codes;

- updating relevant policies and procedures, including any privacy policy and information collection notices to ensure that the prevention, detection, and responses to scams is incorporated;

- uplifting technological and data-sharing capabilities to comply with the new obligations that the Framework imposes, including ensuring they have the ability to report scams to the ACCC within 24 hours of becoming aware of them;

- implementing controls to prevent, detect, disrupt, and report scams in order to comply with the Framework principles;

- developing systems to monitor and track information and other ‘scam intelligence’;

- reviewing and updating governance structures, compliance processes, IDR mechanisms, and relevant internal frameworks to ensure compliance with the Framework principles; and

- engaging in education of key employees to ensure an understanding of potential scam activity and the obligations imposed by the Framework.

If you found this insight article useful and you would like to subscribe to Gadens’ updates, click here.

Authored by:

Daniel Maroske, Partner

Rebecca Laban, Partner

Antoine Pace, Partner

Anna Fanelli, Senior Associate